A Book from the Sky — On Meaning, Memory, and Machines

Art that says nothing— yet means everything.

I first encountered A Book from the Sky in my high school art history class.

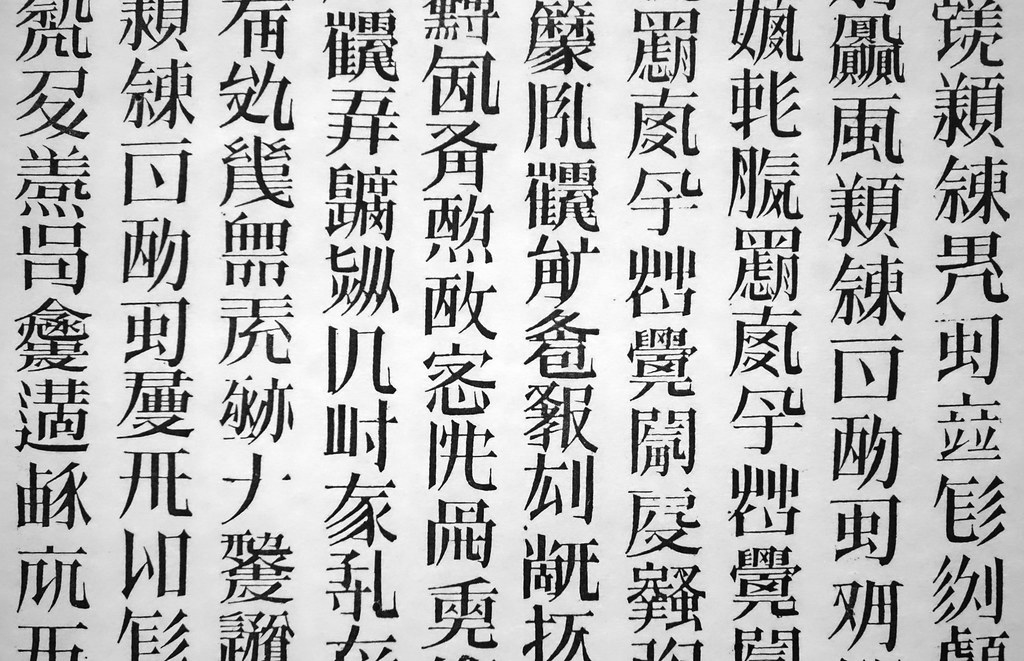

Back then, I was struck by its quiet protest: around 4,000 invented characters, printed in traditional form, that looked unmistakably Chinese— yet meant absolutely nothing. 徐冰 () – Xu Bing had carved them himself, by hand, following the 康熙部首 – () Kangxi radicals. It was art that reveres tradition, while also grieving what’s been lost.

I remember thinking:

this is what happens when meaning is sacrificed for convenience.

When simplification erodes not just a script,

but a culture’s memory.

This week, years later, I saw it in person for the first time on display in the Chengdu Art Museum.

Standing beneath the scrolls, it felt reverent.

Like being in a temple made of language, disassembled and made holy again.

But when I showed a picture to my uncle, he brushed it off.

“Oh, AI can do that now. Just generate nonsense characters.”

I felt something rise up in me— maybe it was anger, maybe it was grief— not because he was technically wrong,

but because something far more important was being dismissed:

Humanity.

Yes, AI can generate thousands of meaningless glyphs.

But Xu Bing chose to.

And that distinction matters.

Meaningless doesn’t mean empty.

Handmade nonsense isn’t the same as automated noise.

One is a reflection.

The other is an output.

4,000 characters— none of them real, all of them intentional.

4,000 characters— none of them real, all of them intentional.

We’re entering an age where AI can mimic any style:

make your voice Attenborough, your selfie Ghibli, your thoughts prose.

But that doesn’t mean art no longer matters.

If anything, it matters more.

Because art is how humans metabolize experience.

It’s how we make sense of what cannot be said.

AI might be able to mimic a scene from Spirited Away—

but it won’t be the animator who walked through a mountain village,

took off his shoes at a shrine,

and sat still long enough to watch the way wind moved through grass.

It won’t be the team at Studio Ghibli,

hand-painting each frame with care,

arguing over light and silence and spirit.

And when I think of Xu Bing—

carving blocks with no meaning,

to protest a system that rewrote an entire language—

I don’t see something replaceable.

I see something irreplaceable.

(Hand-painted by Studio Ghibli artists– from The Secret World of Arrietty)

(Hand-painted by Studio Ghibli artists– from The Secret World of Arrietty)

This isn’t an anti-AI post.

I study AI. I work with it. I believe it can help make life easier, gentler, freer.

But it should be a tool that carries us,

not one that erases us.

And if we let it hollow out the very things that make life worth living—

art, language, culture, reflection—

then we aren’t being efficient.

We’re being forgetful.